Space Force wants six kinds of space weapons—including anti-satellite lasers

Controlling space means "employing kinetic and non-kinetic means to affect adversary capabilities."

Members of the Space Force render a salute during a change of command ceremony July 2, 2024, as Col. Ramsey Horn took the helm of Space Delta 9, the unit that oversees orbital warfare operations at Schriever Space Force Base, Colorado. Credit: US Space Force / Dalton Prejeant

DENVER—The US Space Force lacks the full range of space weapons China and Russia are adding to their arsenals, and military leaders say it's time to close the gap.

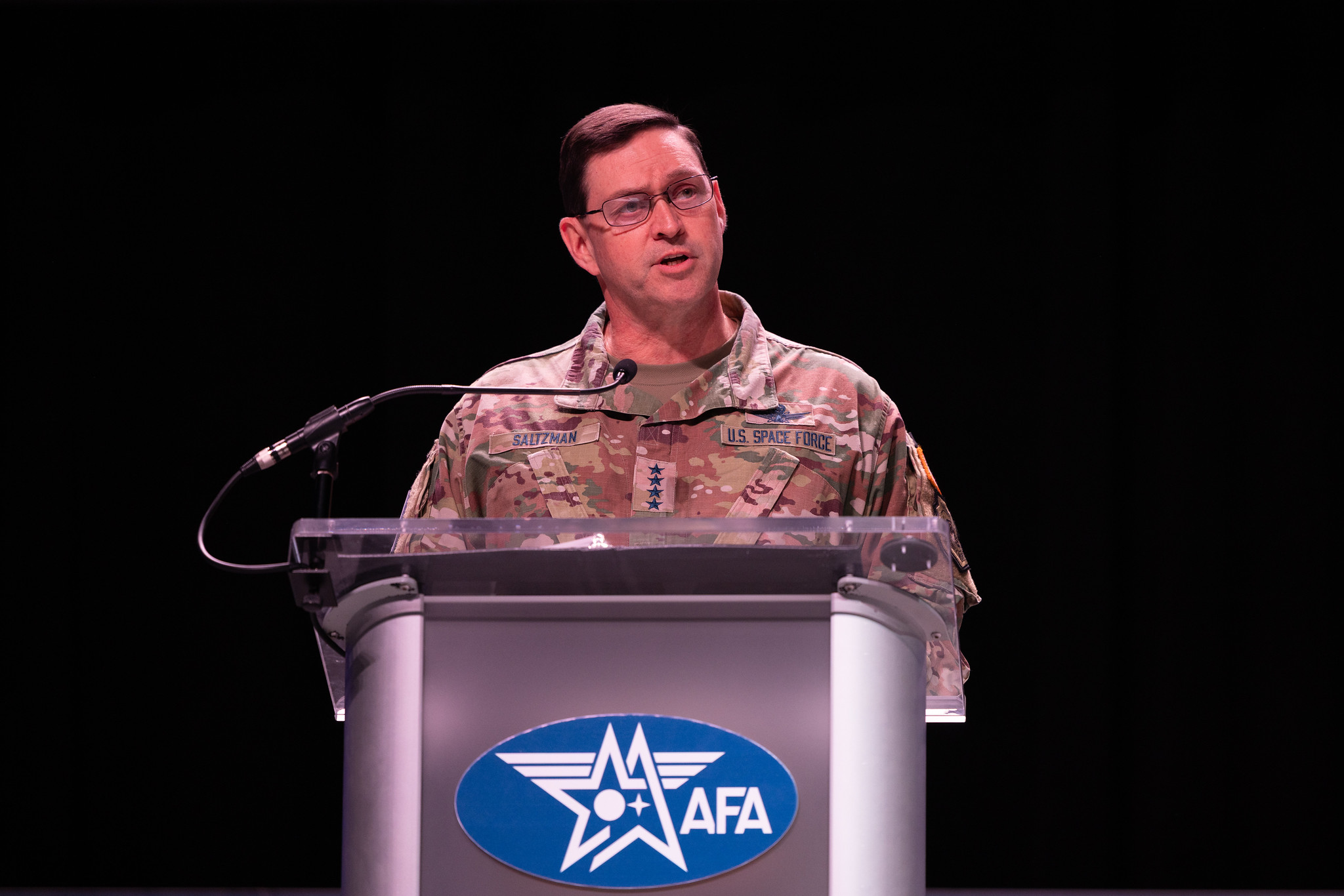

Gen. Chance Saltzman, the Space Force's chief of space operations, told reporters at the Air & Space Forces Association Warfare Symposium last week that he wants more options to present to national leaders if an adversary threatens the US fleet of national security satellites used for surveillance, communication, navigation, missile warning, and perhaps soon, missile defense.

In prepared remarks, Saltzman outlined in new detail why the Space Force should be able to go on the offense in an era of orbital warfare. Later, in a roundtable meeting with reporters, he briefly touched on the how.

The Space Force's top general has discussed the concept of "space superiority" before. This is analogous to air superiority—think of how US and allied air forces dominated the skies in wartime over the last 30 years in places like Iraq, the Balkans, and Afghanistan.

In order to achieve space superiority, US forces must first control the space domain by "employing kinetic and non-kinetic means to affect adversary capabilities through disruption, degradation, and even destruction, if necessary," Saltzman said.

Kinetic? Imagine a missile or some other projectile smashing into an enemy satellite. Non-kinetic? This category involves jamming, cyberattacks, and directed-energy weapons, like lasers or microwave signals, that could disable spacecraft in orbit.

"It includes things like orbital warfare and electromagnetic warfare," Saltzman said. These capabilities could be used offensively or defensively. In December, Ars reported on the military's growing willingness to talk publicly about offensive space weapons, something US officials long considered taboo for fear of sparking a cosmic arms race.

Officials took this a step further at the warfare symposium in Colorado. Saltzman said China and Russia, which military leaders consider America's foremost strategic competitors, are moving ahead of the United States with technologies and techniques to attack satellites in orbit.

This new ocean

For the first time in more than a century, warfare is entering a new physical realm. By one popular measure, the era of air warfare began in 1911, when an Italian pilot threw bombs out of his airplane over Libya during the Italo-Turkish War. Some historians might trace airborne warfare to earlier conflicts, when reconnaissance balloons offered eagle-eyed views of battlefields and troop movements. Land and sea combat began in ancient times.

"None of us were alive when the other domains started being contested," Saltzman said. "It was just natural. It was just a part of the way things work."

Five years since it became a new military service, the Space Force is in an early stage of defining what orbital warfare actually means. First, military leaders stopped considering space as a benign environment, where threats from the harsh environment of space reign supreme.

Artist's illustration of a satellite's destruction in space.

Credit:

Aerospace Corporation

"That shift from benign environment to a war-fighting domain, that was pretty abrupt," Saltzman said. "We had to mature language. We had to understand what was the right way to talk about that progression. So as a Space Force dedicated to it, we've been progressing our vocabulary. We've been saying, 'This is what we want to focus on.'"

"We realized, you know what, defending is one thing, but look at this architecture (from China). They're going to hold our forces at risk. Who's responsible for that? And clearly the answer is the Space Force," Saltzman said. "We say, 'OK, we've got to start to solve for that problem.'"

"Well, how do militaries talk about that? We talk about conducting operations, and that includes offense and defense," he continued. "So it's more of a maturation of the role and the responsibilities that a new service has, just developing the vocabulary, developing the doctrine, operational concepts, and now the equipment and the training. It’s just part of the process."

Of course, this will all cost money. Congress approved a $29 billion budget for the Space Force in 2024, about $4 billion more than NASA received but just 3.5 percent of the Pentagon's overall budget. Frank Kendall, secretary of the Air Force under President Biden, said last year that the Space Force's budget is "going to need to double or triple over time" to fund everything the military needs to do in space.

The six types of space weapons

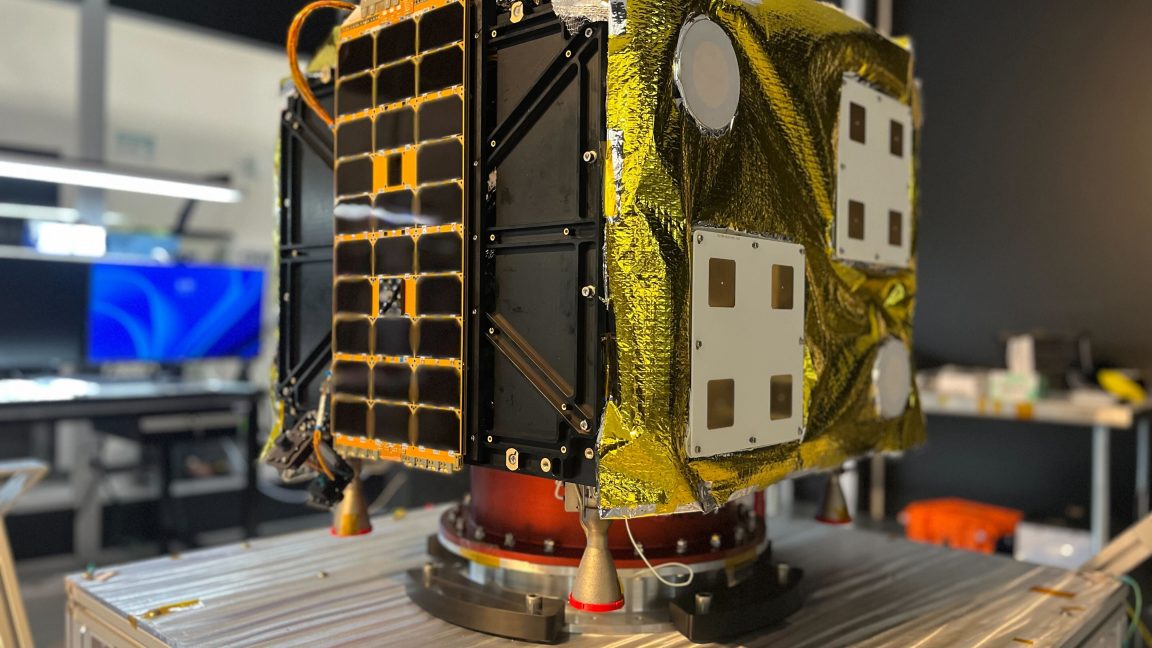

Saltzman said the Space Force categorizes adversarial space weapons in six categories—three that are space-based and three that are ground-based.

"You have directed-energy, like lasers, you have RF (radio frequency) jamming capabilities, and you have kinetic, something that you’re trying to destroy physically," Saltzman said. These three types of weapons could be positioned on the ground or in space, getting to Saltzman's list of six categories.

"We're seeing in our adversary developmental capabilities, they're pursuing all of those," Saltzman said. "We're not pursuing all of those yet."

But Saltzman argued that maybe the United States should. "There are good reasons to have all those categories," he said. Targeting an enemy satellite in low-Earth orbit, just a few hundred miles above the planet, requires a different set of weapons than a satellite parked more than 22,000 miles up—roughly 36,000 kilometers—in geosynchronous orbit.

China is at the pinnacle of the US military's threat pyramid, followed by Russia and less sophisticated regional powers like North Korea and Iran.

"Really, what's most concerning... is the mix of weapons," Saltzman said. "They are pursuing the broadest mix of weapons, which means they're going to hold a vast array of targets at risk if we can't defeat them. So our focus out of the gate has been on resiliency of our architectures. Make the targeting as hard on the adversary as possible."

Gen. Chance Saltzman, the chief of Space Operations, speaks at the Air & Space Forces Association's Warfare Symposium on March 3, 2025.

Credit:

Jud McCrehin / Air & Space Forces Association

About a decade ago, the military recognized an imperative to transition to a new generation of satellites. Where they could, Pentagon officials replaced or complemented their fleets of a few large multibillion-dollar satellites with constellations of many more cheaper, relatively expendable satellites. If an adversary took out just one of the military's legacy satellites, commanders would feel the pain. But the destruction of multiple smaller satellites in the newer constellations wouldn't have any meaningful effect.

That's one of the reasons the military's Space Development Agency has started launching a network of small missile-tracking satellites in low-Earth orbit, and it's why the Pentagon is so interested in using services offered by SpaceX's Starlink broadband constellation. The Space Force is looking at ways to revamp its architecture for space-based navigation by potentially augmenting or replacing existing GPS satellites with an array of positioning platforms in different orbits.

"If you can disaggregate your missions from a few satellites to many satellites, you change the targeting calculus," Saltzman said. "If you can make things maneuverable, then it's harder to target, so that is the initial effort that we invested heavily on in the last few years to make us more resilient."

Now, Saltzman said, the Space Force must go beyond reshaping how it designs its satellites and constellations to respond to potential threats. These new options include more potent offensive and defensive weapons. He declined to offer specifics, but some options are better than others.

The cost of destruction

“Generally in a military setting, you don’t say, 'Hey, here's all the weapons, and here's how I'm going to use them, so get ready,'" Saltzman said. "That's not to our advantage... but I will generally [say] that I am far more enamored by systems that deny, disrupt, [and] degrade. There's a lot of room to leverage systems focused on those 'D words.' The destroy word comes at a cost in terms of debris."

A high-speed collision between an interceptor weapon and an enemy satellite would spread thousands of pieces of shrapnel across busy orbital traffic lanes, putting US and allied spacecraft at risk.

"We may get pushed into a corner where we need to execute some of those options, but I’m really focused on weapons that deny, disrupt, degrade," Saltzman said.

This tenet of environmental stewardship isn't usually part of the decision-making process for commanders in other military branches, like the Air Force or the Navy. "I tell my air-breathing friends all the time: When you shoot an airplane down, it falls out of your domain," Saltzman said.

China now operates more than 1,000 satellites, and more than a third of these are dedicated to intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions. China's satellites can collect high-resolution spy imagery and relay the data to terrestrial forces for military targeting. The Chinese "space-enabled targeting architecture" is "pretty impressive," Saltzman said.

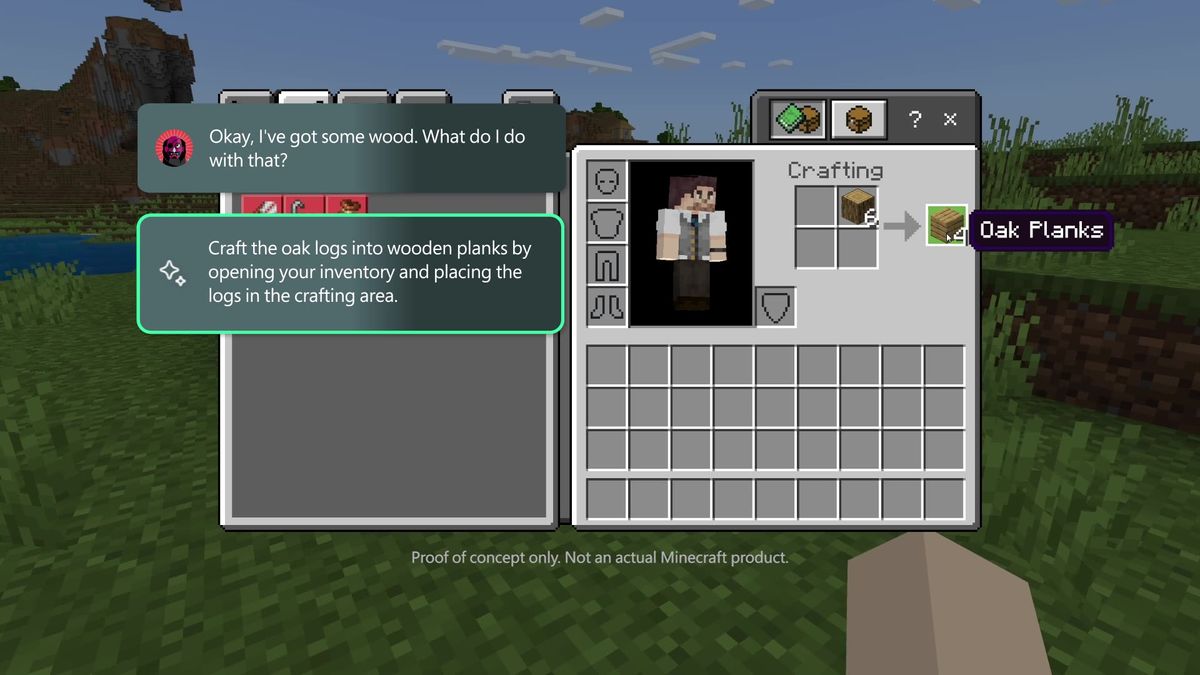

This slide from a presentation by Space Systems Command illustrates a few of the counter-space weapons fielded by China and Russia.

Credit:

Space Systems Command

"We have a responsibility not only to defend the assets in space but to protect the war-fighter from space-enabled attack," said Lt. Gen. Doug Schiess, a senior official at US Space Command. "What China has done with an increasing launch pace is put up intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance satellites that can then target our naval forces, our land forces, and our air forces at much greater distance. They've essentially built a huge kill chain, or kill web, if you will, to be able to target our forces much earlier."

China's aerospace forces have either deployed or are developing direct-ascent anti-satellite missiles, co-orbital satellites, electronic warfare platforms like mobile jammers, and directed-energy, or laser, systems, according to a Pentagon report on China's military and security advancements. These weapons can reach targets from low-Earth orbit all the way up to geosynchronous orbit.

In his role as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Saltzman advises the White House on military matters. Like most military commanders, he said he wants to offer his superiors as many options as possible. "The more weapons mix we have, the more options we can offer the president," Saltzman said.

The US military has already demonstrated it can shoot down a satellite with a ground-based interceptor, and the Space Force is poised to field new ground-based satellite jammers in the coming months. The former head of the Space Force, Gen. Jay Raymond, told lawmakers in 2021 that the military was developing directed-energy weapons to assure dominance in space, although he declined to discuss details in an unclassified hearing.

So the Pentagon is working on at least three of the six space weapons categories identified by Saltzman. China and Russia appear to have the edge in space-based weapons, at least for now.

In the last several years, Russia has tested a satellite that can fire a projectile capable of destroying another spacecraft in orbit, an example of a space-based kinetic weapon. Last year, news leaked that US intelligence officials are concerned about Russian plans to put a nuclear weapon in orbit. China launched a satellite named Shijian-17 in 2016 with a robotic arm that could be used to grapple and capture other satellites in space. Then, in 2021, China launched Shijian-21, which docked with a defunct Chinese satellite to take over its maneuvering and move it to a different orbit.

There's no evidence that the US Space Force has demonstrated kinetic space-based anti-satellite weapons, and Pentagon officials have roundly criticized the possibility of Russia placing a nuclear weapon in space. But the US military might soon develop space-based interceptors as part of the Trump administration's "Golden Dome" missile defense shield. These interceptors might also be useful in countering enemy satellites during conflict.

The Sodium Guidestar at the Air Force Research Laboratory's Starfire Optical Range in New Mexico. Researchers with AFRL's Directed Energy Directorate use the Guidestar laser for real-time, high-fidelity tracking and imaging of satellites too faint for conventional adaptive optical imaging systems.

Credit:

US Air Force

The Air Force used a robotic arm on a 2007 technology demonstration mission to snag free-flying satellites out of orbit, but this was part of a controlled experiment with a spacecraft designed for robotic capture. Several companies, such as Maxar and Northrop Grumman, are developing robotic arms that could grapple "non-cooperative" satellites in orbit.

While the destruction of an enemy satellite is likely to be the Space Force's last option in a war, military commanders would like to be able to choose to do so. Schiess said the military "continues to have gaps" in this area.

"With destroy, we need that capability, just like any other domain needs that capability, but we have to make sure that we do that with responsibility because the space domain is so important," Schiess said.

Matching the rhetoric of today

The Space Force's fresh candor about orbital warfare should be self-evident, according to Saltzman. "Why would you have a military space service if not to execute space control?"

This new comfort speaking about space weapons comes as the Trump administration strikes a more bellicose tone in foreign policy and national security. Pete Hegseth, Trump's secretary of defense, has pledged to reinforce a "warrior ethos" in the US armed services.

Space Force officials are doing their best to match Hegseth's rhetoric.

"Every guardian is a war-fighter, regardless of your functional specialty, and every guardian contributes to Space Force readiness," Saltzman said. Guardian is the military's term for a member of the Space Force, comparable to airmen, sailors, soldiers, and marines. "Whether you built the gun, pointed the gun, or pulled the trigger, you are a part of combat capability."

Echoing Hegseth, the senior enlisted member of the Space Force, Chief Master Sgt. John Bentivegna, said he's focused on developing a "war-fighter ethos" within the service. This involves training on scenarios of orbital warfare, even before the Space Force fields any next-generation weapons systems.

"As Gen. Saltzman is advocating for the money and the resources to get the kit, the culture, the space-minded war-fighter, that work has been going on and continues today," Bentivegna said.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/13/764/n/1922729/4c26cfa167d313d93a57b8.85428907_.webp)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/12/103/n/1922153/5e6cd9bf67d234e03b5bf6.14130631_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/01/29/984/n/1922153/3153712665b828a277d2c6.55118005_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/11/22/933/n/24155406/398759ae6740f663d755c4.12400021_.png)