With new contracts, SpaceX will become the US military’s top launch provider

The military's stable of certified rockets will include Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, Vulcan, and New Glenn.

A SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket lifts off on June 25, 2024, with a GOES weather satellite for NOAA. Credit: SpaceX

The US Space Force announced Friday it selected SpaceX, United Launch Alliance, and Blue Origin for $13.7 billion in contracts to deliver the Pentagon's most critical military to orbit into the early 2030s.

These missions will launch the government's heaviest national security satellites, like the National Reconnaissance Office's large bus-sized spy platforms, and deploy them into bespoke orbits. These types of launches often demand heavy-lift rockets with long-duration upper stages that can cruise through space for six or more hours.

The contracts awarded Friday are part of the next phase of the military's space launch program once dominated by United Launch Alliance, the 50-50 joint venture between legacy defense contractors Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

After racking up a series of successful launches with its Falcon 9 rocket more than a decade ago, SpaceX sued the Air Force for the right to compete with ULA for the military's most lucrative launch contracts. The Air Force relented in 2015 and allowed SpaceX to bid. Since then, SpaceX has won more than 40 percent of missions the Pentagon has ordered through the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program, creating a relatively stable duopoly for the military's launch needs.

The Space Force took over the responsibility for launch procurement from the Air Force after its creation in 2019. The next year, the Space Force signed another set of contracts with ULA and SpaceX for missions the military would order from 2020 through 2024. ULA's new Vulcan rocket initially won 60 percent of these missions—known as NSSL Phase 2—but the Space Force reallocated a handful of launches to SpaceX after ULA encountered delays with Vulcan.

ULA's Vulcan and SpaceX's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets will launch the remaining 42 Phase 2 missions over the next several years, then move on to Phase 3, which the Space Force announced Friday.

Spreading the wealth

This next round of Space Force launch contracts will flip the script, with SpaceX taking the lion's share of the missions. The breakdown of the military's new firm fixed-price launch agreements goes like this:

- SpaceX will get 28 missions worth approximately $5.9 billion

- ULA will get 19 missions worth approximately $5.4 billion

- Blue Origin will get seven missions worth approximately

That equates to a 60-40 split between SpaceX and ULA for the bulk of the missions. Going into the competition, military officials set aside seven additional missions to launch with a third provider, allowing a new player to gain a foothold in the market. The Space Force reserves the right to reapportion missions between the three providers if one of them runs into trouble.

The Pentagon confirmed an unnamed fourth company also submitted a proposal, but wasn't selected for Phase 3.

Rounded to the nearest million, the contract with SpaceX averages out to $212 million per launch. For ULA, it's $282 million, and Blue Origin's price is $341 million per launch. But take these numbers with caution. The contracts include a lot of bells and whistles, pricing them higher than what a commercial customer might pay.

According to the Pentagon, the contracts provide "launch services, mission unique services, mission acceleration, quick reaction/anomaly resolution, special studies, launch service support, fleet surveillance, and early integration studies/mission analysis."

Essentially, the Space Force is paying a premium to all three launch providers for schedule priority, tailored solutions, and access to data from every flight of each company's rocket, among other things.

New Glenn lifts off on its debut flight.

Credit:

Blue Origin

"Winning 60% percent of the missions may sound generous, but the reality is that all SpaceX competitors combined cannot currently deliver the other 40%!," Elon Musk, SpaceX's founder and CEO, posted on X. "I hope they succeed, but they aren’t there yet."

This is true if you look at each company's flight rate. SpaceX has launched Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets 140 times over the last 365 days. These are the flight-proven rockets SpaceX will use for its share of Space Force missions.

ULA has logged four missions in the same period, but just one with the Vulcan rocket it will use for future Space Force launches. And Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos's space company, launched the heavy-lift New Glenn rocket on its first test flight in January.

"We are proud that we have launched 100 national security space missions and honored to continue serving the nation with our new Vulcan rocket," said Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and CEO, in a statement.

ULA used the Delta IV and Atlas V rockets for most of the missions it has launched for the Pentagon. The Delta IV rocket family is now retired, and ULA will end production of the Atlas V rocket later this year. Now, ULA's Vulcan rocket will take over as the company's sole launch vehicle to serve the Pentagon. ULA aims to eventually ramp up the Vulcan launch cadence to fly up to 25 times per year.

After two successful test flights, the Space Force formally certified the Vulcan rocket last week, clearing the way for ULA to start using it for military missions in the coming months. While SpaceX has a clear advantage in number of launches, schedule assurance, and pricing—and reliability comparable to ULA—Bruno has recently touted the Vulcan rocket's ability to maneuver over long periods in space as a differentiator.

"This award constitutes the most complex missions required for national security space," Bruno said in a ULA press release. "Vulcan continues to use the world’s highest energy upper stage: the Centaur V. Centaur V's unmatched flexibility and extreme endurance enables the most complex orbital insertions continuing to advance our nation’s capabilities in space."

Blue Origin's New Glenn must fly at least one more successful mission before the Space Force will certify it for Lane 2 missions. The selection of Blue Origin on Friday suggests military officials believe New Glenn is on track for certification by late 2026.

"Honored to serve additional national security missions in the coming years and contribute to our nation’s assured access to space," Dave Limp, Blue Origin's CEO, wrote on X. "This is a great endorsement of New Glenn's capabilities, and we are committed to meeting the heavy lift needs of our US DoD and intelligence agency customers."

Navigating NSSL

There's something you must understand about the way the military buys launch services. For this round of competition, the Space Force divided the NSSL program into two lanes.

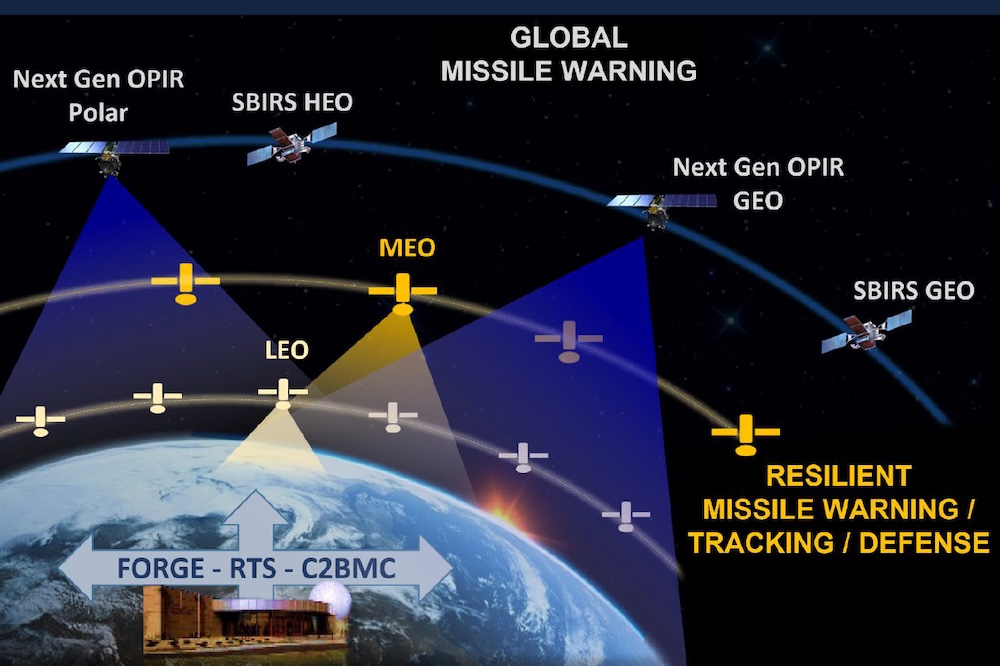

Friday's announcement covers Lane 2 for traditional military satellites that operate thousands of miles above the Earth. This bucket includes things like GPS navigation satellites, NRO surveillance and eavesdropping platforms, and strategic communications satellites built to survive a nuclear war. The Space Force has a low tolerance for failure with these missions. Therefore, the military requires rockets be certified before they can launch big-ticket satellites, each of which often cost hundreds of millions, and sometimes billions, of dollars.

The Space Force required all Lane 2 bidders to show their rockets could reach nine "reference orbits" with payloads of a specified mass. Some of the orbits are difficult to reach, requiring technology that only SpaceX and ULA have demonstrated in the United States. Blue Origin plans to do so on a future flight.

This image shows what the Space Force's fleet of missile warning and missile tracking satellites might look like in 2030, with a mix of platforms in geosynchronous orbit, medium-Earth orbit, and low-Earth orbit. The higher orbits will require launches by "Lane 2" providers.

Credit:

Space Systems Command

The military projects to order 54 launches in Lane 2 from this year through 2029, with announcements each October of exactly which missions will go to each launch provider. This year, it will be just SpaceX and ULA. The Space Force said Blue Origin won't be eligible for firm orders until next year. The missions would launch between 2027 and 2032.

"America leads the world in space launch, and through these NSSL Phase 3 Lane 2 contracts, we will ensure continued access to this vital domain," said Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration. "These awards bolster our ability to launch critical defense satellites while strengthening our industrial base and enhancing operational readiness."

Lane 1 is primarily for missions to low-Earth orbit. These payloads include tech demos, experimental missions, and the military's mega-constellation of missile tracking and data relay satellites managed by the Space Development Agency. For Lane 1 missions, the Space Force won't levy the burdensome certification and oversight requirements it has long employed for national security launches. The Pentagon is willing to accept more risk with Lane 1, encompassing at least 30 missions through the end of the 2020s, in an effort to broaden the military's portfolio of launch providers and boost competition.

Last June, Space Systems Command chose SpaceX, ULA, and Blue Origin for eligibility to compete for Lane 1 missions. SpaceX won all nine of the first batch of Lane 1 missions put up for bids. The military recently added Rocket Lab's Neutron rocket and Stoke Space's Nova rocket to the Lane 1 mix. Neither of those rockets have flown, and they will need at least one successful launch before approval to fly military payloads.

The Space Force has separate contract mechanisms for the military's smallest satellites, which typically launch on SpaceX rideshare missions or dedicated launches with companies like Rocket Lab and Firefly Aerospace.

Military leaders like having all these options, and would like even more. If one launch provider or launch site is unavailable due to a technical problem—or, as some military officials now worry, an enemy attack—commanders want multiple backups in their toolkit. Market forces dictate that more competition should also lower prices.

"A robust and resilient space launch architecture is the foundation of both our economic prosperity and our national security," said US Space Force Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman. "National Security Space Launch isn't just a program; it's a strategic necessity that delivers the critical space capabilities our warfighters depend on to fight and win."

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/27/776/n/49351773/1c19936567e58d1c5c6c01.86394536_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/21/942/n/1922153/a404f57067dddc11928eb9.35389661_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/04/02/061/n/49351765/e4176f9167edd650319326.42956894_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/26/842/n/49351761/552865fa67e451bdbb8847.65246064_.jpg)